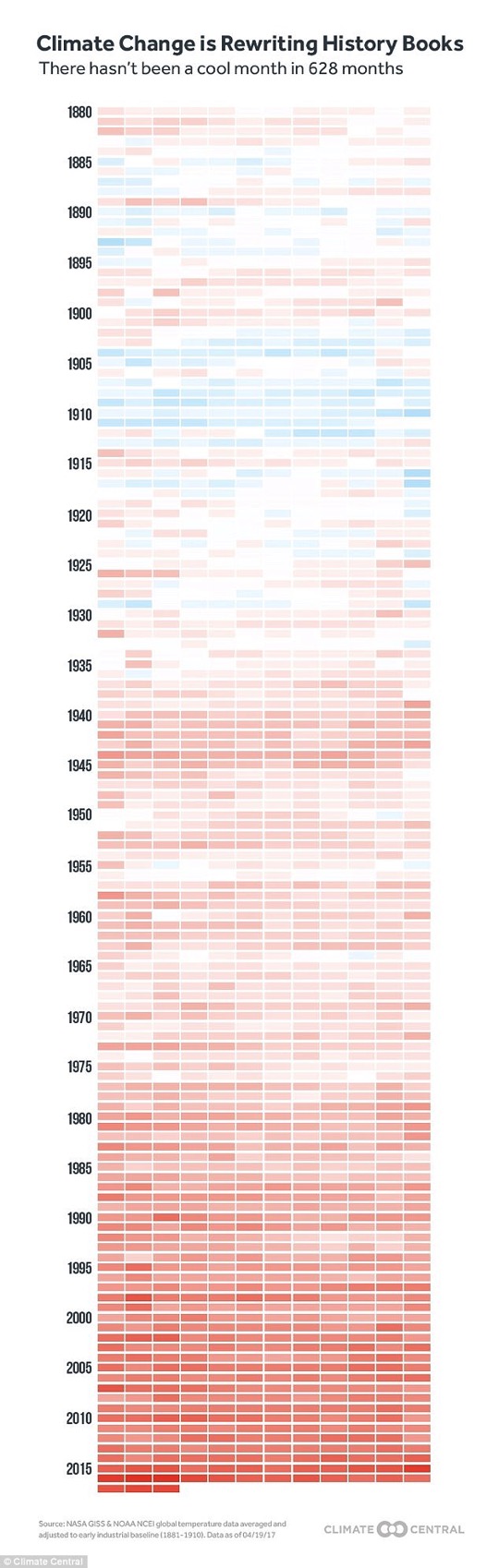

Global Warming Chart 1880 - 2017

Scientists have created a global temperature chart that maps the average monthly temperature from 1880 to 2015. The result shows that every single month has been warmer than the early industrial baseline for more than half a century.

The map was created by Climate Central, based on Nasa and NOAA global temperature data, relative to a baseline of average global temperatures between 1881 and 1910.

On the chart, each month is represented by a box.

Light blue colours depict months that were cooler than average, while red boxes represent months that were much hotter than average.

The Unfolding Tragedy of Climate Change in Bangladesh

Bangladesh sits at the head of the Bay of Bengal, astride the largest river delta on Earth, formed by the junction of the Brahmaputra, Ganges, and Meghna rivers. Nearly one-quarter of Bangladesh is less than seven feet about sea level; two-thirds of the country is less than 15 feet above sea level. Most Bangladeshis live along coastal areas where alluvial delta soils provide some of the best farmland in the country.

Sea surface temperatures in the shallow Bay of Bengal have significantly increased, which, scientists believe, has caused Bangladesh to suffer some of the fastest recorded sea level rises in the world. Storm surges from more frequent and stronger cyclones push walls of water 50 to 60 miles up the Delta’s rivers.

At the same time, melting of glaciers and snowpack in the Himalayas, which hold the third largest body of snow on Earth, has swollen the rivers that flow into Bangladesh from Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and India. So too have India’s water policies. India diverts large quantities of water for irrigation during the dry season and releases most water during the monsoon season.

According to the Bangladesh government’s 2009 Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan, “in an ‘average’ year, approximately one quarter of the country is inundated.” Every four to five years, “there is a severe flood that may cover over 60% of the country.” Rapid erosion of coastal areas has inundated dozens of islands in the Bay. For example, Sandwip Island, near Chittagong, has lost 90 percent of its original 23-square-miles—mostly in the last two decades.

Climate change in Bangladesh has started what may become the largest mass migration in human history. In recent years, riverbank erosion has annually displaced between 50,000 and 200,000 people. The population of what the Bangladesh government calls “immediately threatened” islands, called “chars,” exceeds four million.

The Bangladesh riverine environment is so dynamic that, as chars wash away, the process of accretion creates new chars downstream. Land is so scarce and the population so dense that the displaced people try to eke out an existence on these new, highly unstable sand bars.

Already, the intruding sea has contaminated groundwater, which supplies drinking water for coastal regions, and degraded farmland, rendering it less fertile and eventually barren.

It is not just people who are affected. The Sundarbans, the largest mangrove forest in the world and a World Heritage Site, lies in the delta of the Ganges River in Bangladesh and India. Home to the iconic Bengal tiger, the Sundarbans also play a critical role in protecting Bangladesh’s coastal areas from storm surges caused by cyclones.

Nevertheless, across coastal Bangladesh, sea-level rise, exacerbated by the conversion of mangrove forest for agricultural production and shrimp farming, has resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of acres of mangroves. In the Sundarbans, the number of tigers has plummeted. The World Wildlife Fund predicts that the tiger may become extinct. Further loss of mangrove habitat, especially in the Sundarbans, also means that Bangladesh will lose one of its last natural defenses against climate change-induced super-cyclones.

No comments:

Post a Comment